Current work

The olfactory bulb input-output transformation

My former colleague Tobias Ackels imaged the inputs and output responses of olfactory bulb glomeruli to a bank of nearly 50 odours. These data allowed him to observe how odour representations are transformed from the input to the output of the bulb. By using analytical and numerical tools based on a simple linear model of the olfactory bulb, I’m helping him understand how this transformation comes about.

Past projects

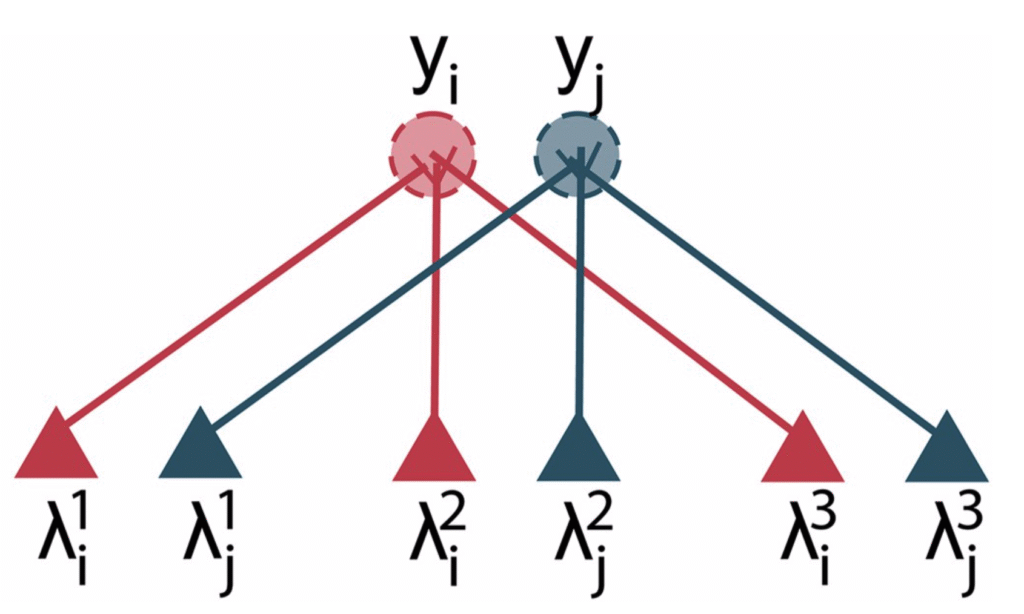

Inference with correlated priors using sister cells

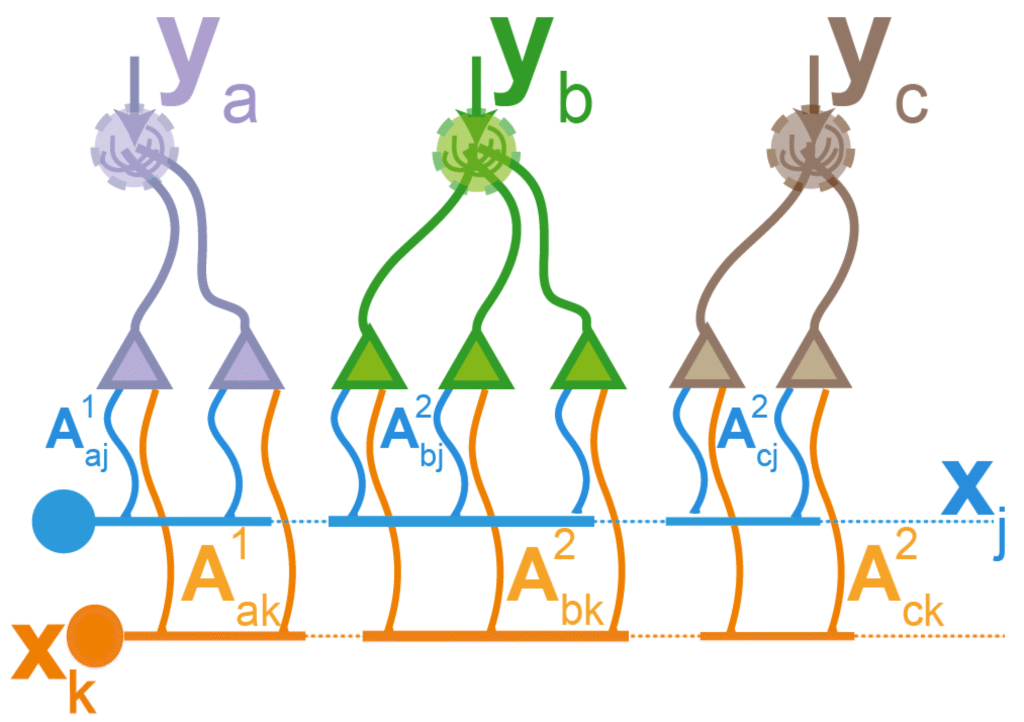

The smell of coffee in the morning is often accompanied by that of toast. Including such prior would improve inferential accuracy. However, the naive implementation of such correlated priors requires neurons that represent these objects to be connected, which can pose architectural difficulties. In work that we presented at NeurIPS 2025 (openreview, poster) we showed how modifying standard olfactory bulb inference circuitry to incorporate sister cells naturally allows inference with correlated priors, but without requiring direct interactions between neurons representing olfactory objects. Instead, correlation information is stored in the way these neurons connect to the sister cells.

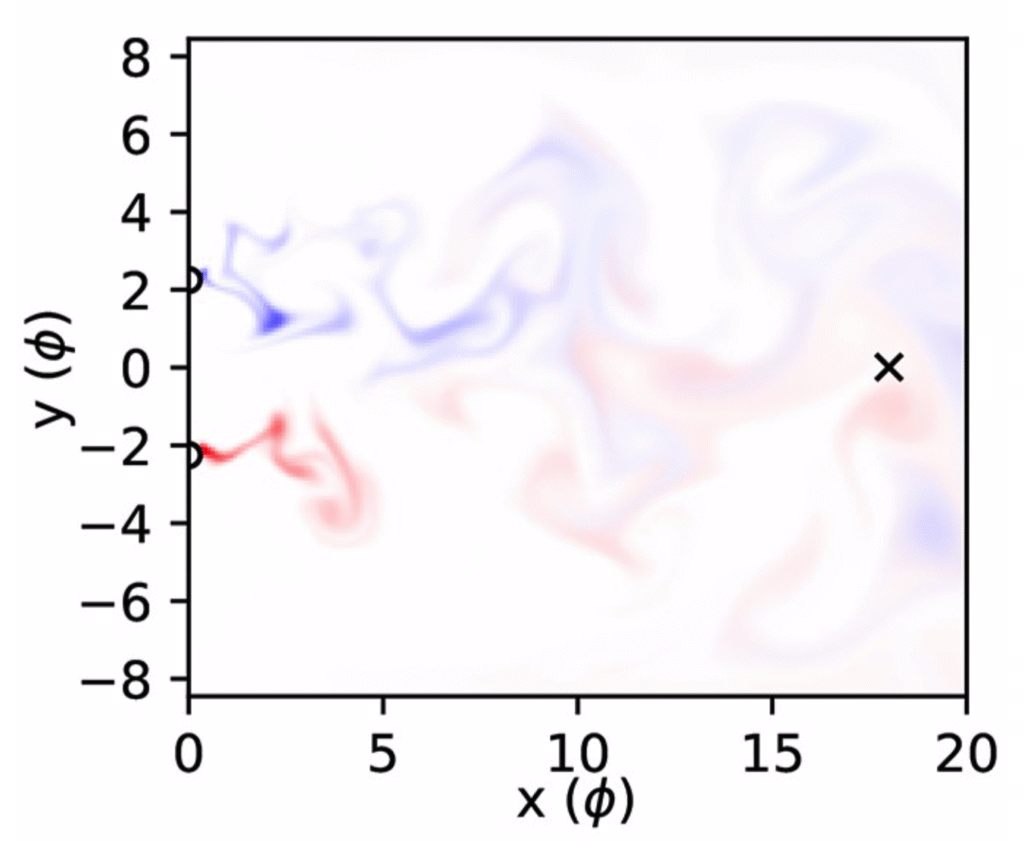

Quantifying spatial information in odour plumes

The plumes generated by two odour sources become less correlated as sources get farther apart, indicating that correlations contain spatial information. In this study from 2025 we showed how to quantify this spatial information, and found that high frequency components are more informative than low frequency components when sources are close together. This suggests that the high frequency odour acuity observed in mice could be useful for odour source localization.

Tufted cells for speed, mitral cells for recall.

The olfactory bulb has two types of projection neurons: tufted cells which respond quickly and vigorously to odour presentation, and mitral cells which produce slower, more nuanced responses. In work that I presented at COSYNE 2023 (abstract, poster), I provided a normative explanation for these and other properties of the two populations using a common probabilistic framework in which tufted cells produce a rapid sketch of the olfactory input, which mitral cells use a scaffold and combine with higher-order olfactory priors such as those provided by the memory system to perform more precise inference.

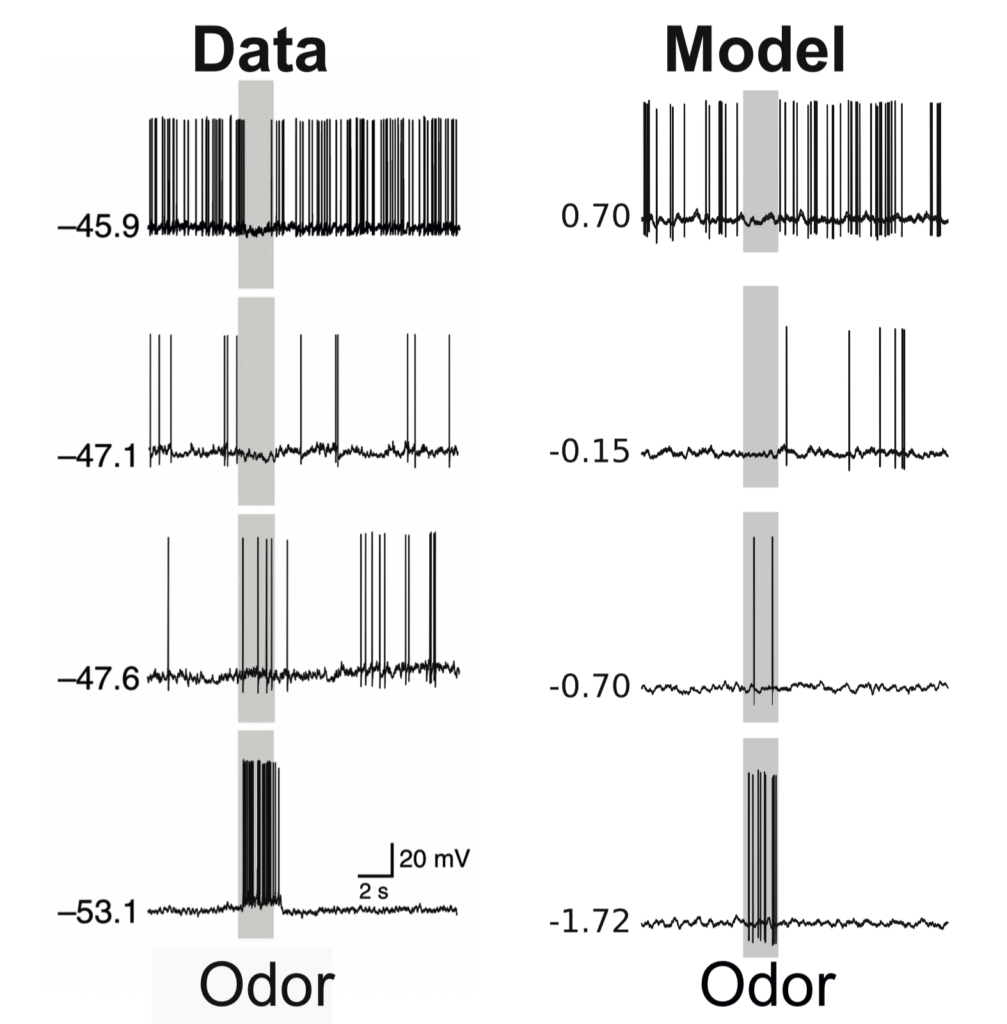

‘Silent’ cells and common feature subtraction

Neural recordings can often be biased towards responsive neurons. Prior experimental work had shown that when recordings are performed in an unbiased way, odour responses are dominated by cells which are silent during the baseline period, and vise versa. In work presented at COSYNE 2022 (abstract, poster), I provided a normative explanation for these findings as implementing “common feature subtraction“, wherein the olfactory system distinguishes odours from background air and gradually subtracts the odour components common to recent sniffs to emphasize the unique olfactory features present in each sniff.

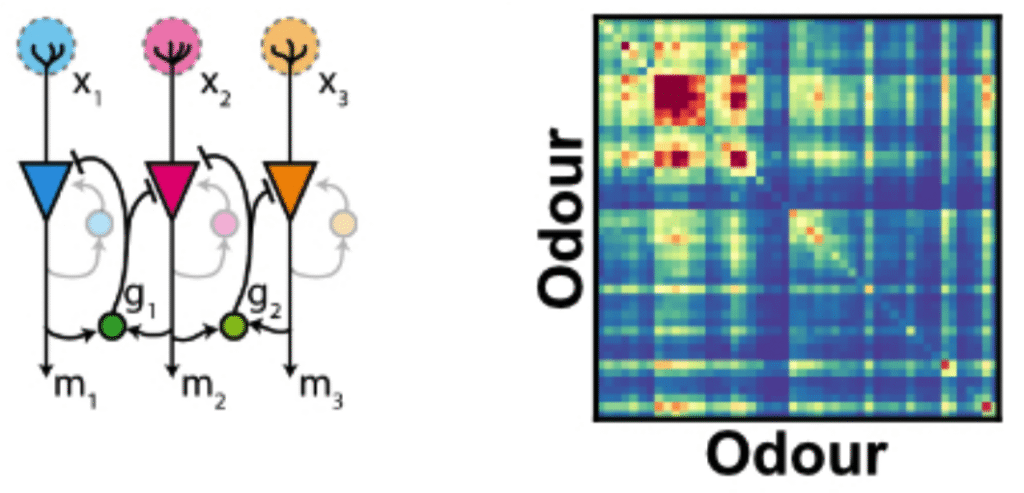

Sister cells can distribute inference connectivity

In the olfactory bulb, sensory signals converge by receptor type onto dozens of “sister cells” which thus receive the same input, but connect differently to local interneurons. In this study from 2022 we suggested that this architecture could allow the bulb to sparsify the dense connectivity required for inference by distributing it among the sister cells, with a population of glomerular interneurons ensuring sisters converge to the same inferred odour.

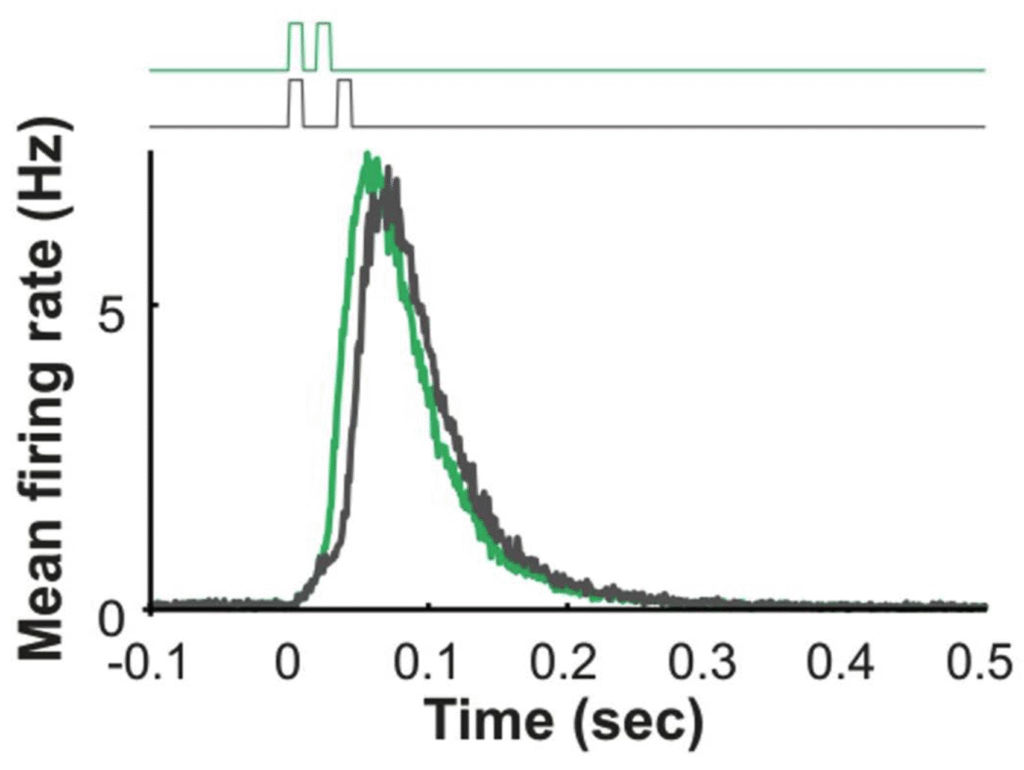

Distinguishing fast odours with slow sensors

Our intuition tells us that olfaction is a slow sense, operating on the order of seconds. In this 2021 study, my colleagues showed that mice could be trained to distinguish odour concentration fluctuations at up to 40 Hz. Reviewers were initially skeptical that this could be done, since signalling by individual olfactory sensory neurons happens more slowly. My contribution was to show in simulation that such discriminations could be performed even with slow sensory neurons, as long as there were enough available to signal a given fluctuation.

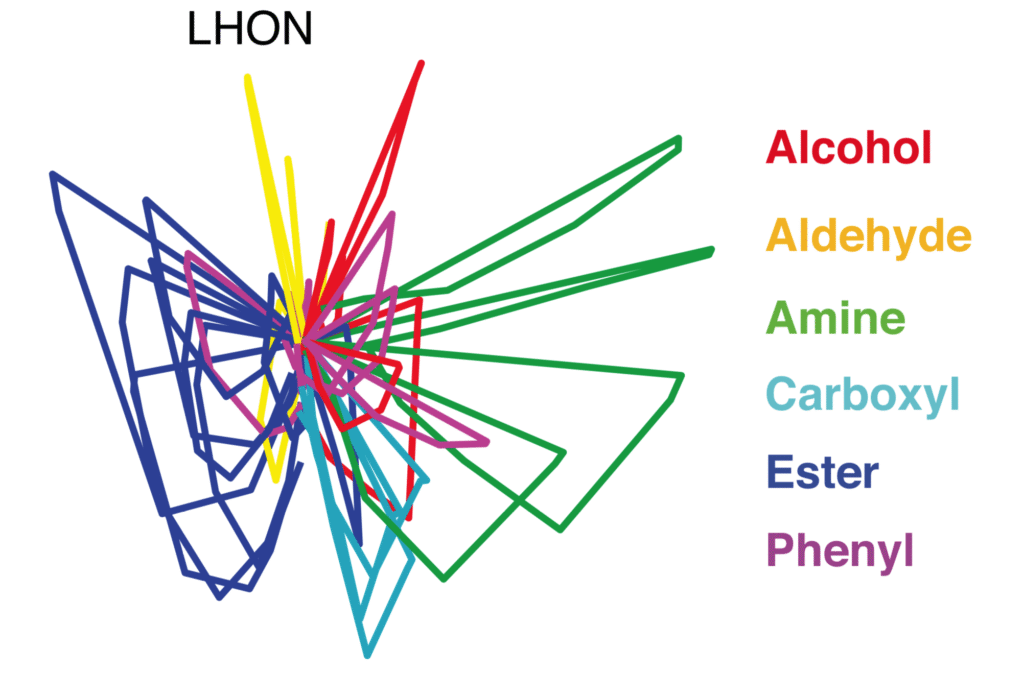

Coding of odour category by the lateral horn

In the insect olfactory system, innate odour associations are processed by a stucture called the lateral horn. My contribution to this extensive 2019 study of this structure in fruitflies was to examine the odour coding properties of lateral horn neurons. We observed that representations of odour category were better separated in this structure than upstream areas, facilitating accurate decoding.

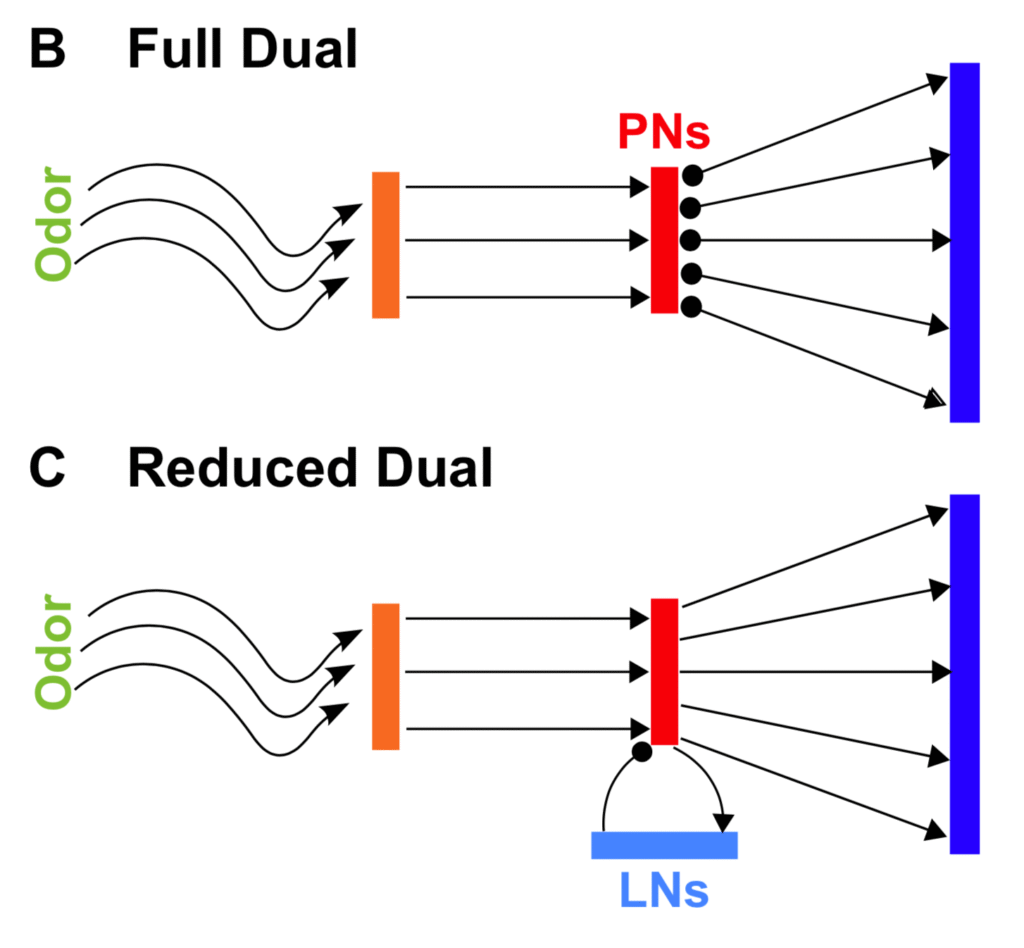

Olfactory inference by convex duality

In this work from 2014 we formulated olfaction as in inference computation and showed how solving the dual optimization problem yields an architecture and dynamics qualitatively similar to many olfactory systems. The locust olfactory system that we were interested in understanding wasn’t large enough to accommodate the resulting algorithm in full, so we showed how it could approximate the full solution by continuously learning the statistics of the environment using a biological plausible implementation of expectation maximization.

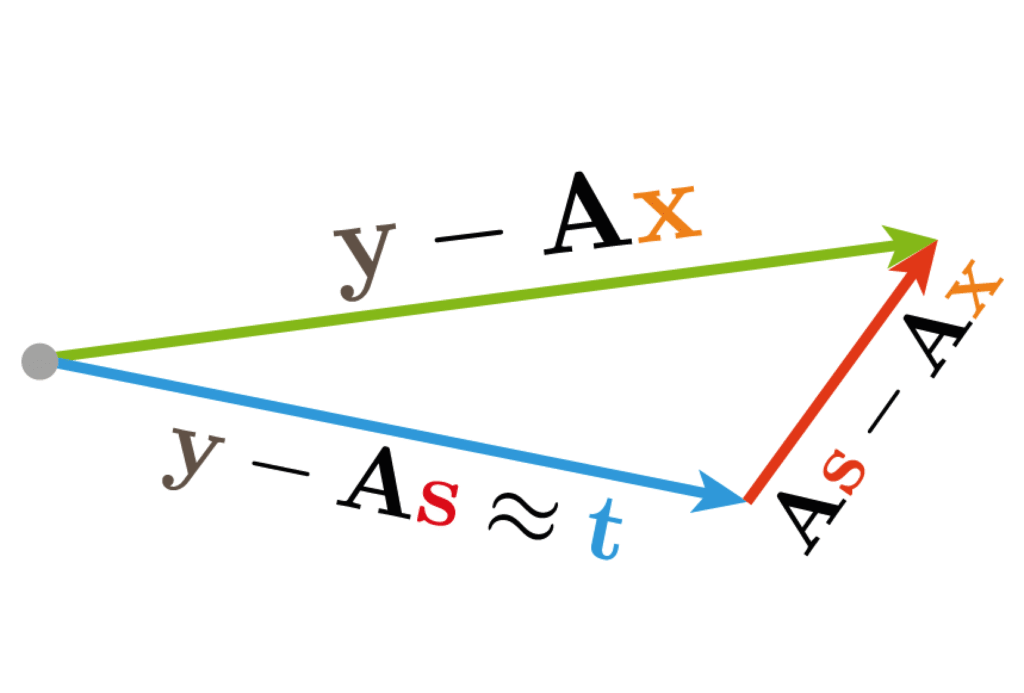

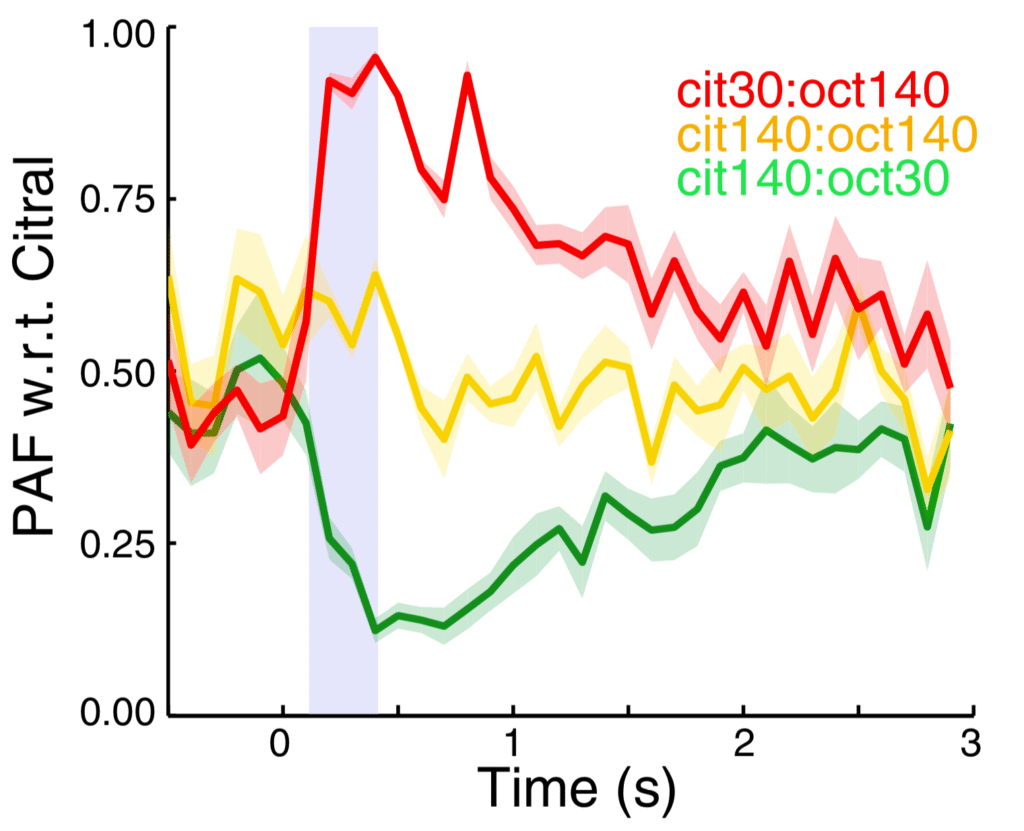

Quantifying nonlinear dimensionality reduction

During my Ph.D. I had the privelage of helping Kai Shen analyze his data on the mixture responses of the locust olfactory system. He had quantified these with a variety of linear and non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques, and I wondered whether the qualitative impressions derived from these held in the full space of responses. I therefore produced a variety of measures to quantify those qualitative impressions, some of which we included in our publication. The example on the left relates three binary mixture responses to the component responses by projecting the mixture responses onto the plane spanned by the components.