On the Discord we’ve been discussing “Toy Models of Superposition” form Anthropic. It’s a long blog post, so these are my running notes to get people (and myself) up to speed if they’ve missed a week or two of the discussion.

As I’ve started these notes midway through the discussion, I’ll start on the latest section and fill in the rest over time.

Problem Setup

The authors’ basic aim is to demonstrate “superposition“: neurons representing multiple input features.

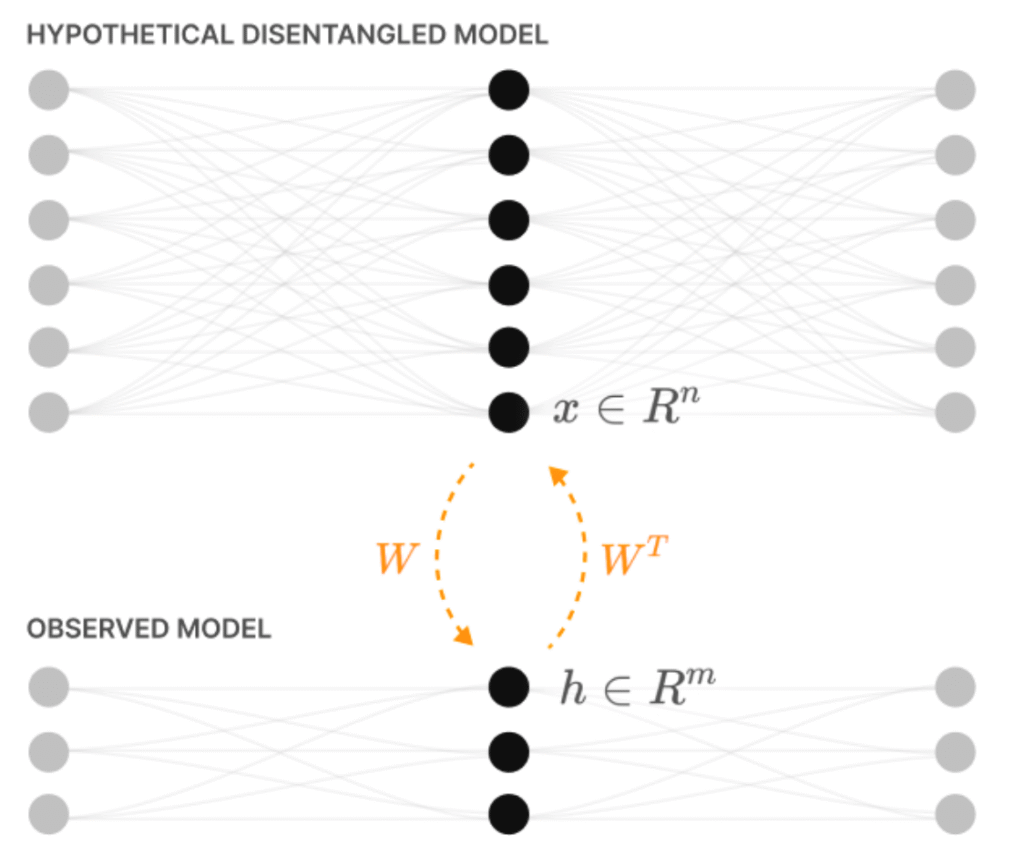

They bring this about by considering the compression of high-dimensional input features into a low dimensional hidden layer, and then back again. Because of their interest in interpretability, they imagine the high-dimensional features correspond to the disentangled representations of the environment that a hypothetical very large neural network would use. Such a network would be able to explain its sensory input as the presence of a number of features that correspond to interpretable aspects of the environment.

In this larger network, each hidden layer neuron represents one feature. In a smaller network, the hidden layer neurons have to represent multiple features, producing superposition.

They study the input features that each hidden layer neuron responds to, and how this changes as the statistics of the input are altered.

Model and Loss

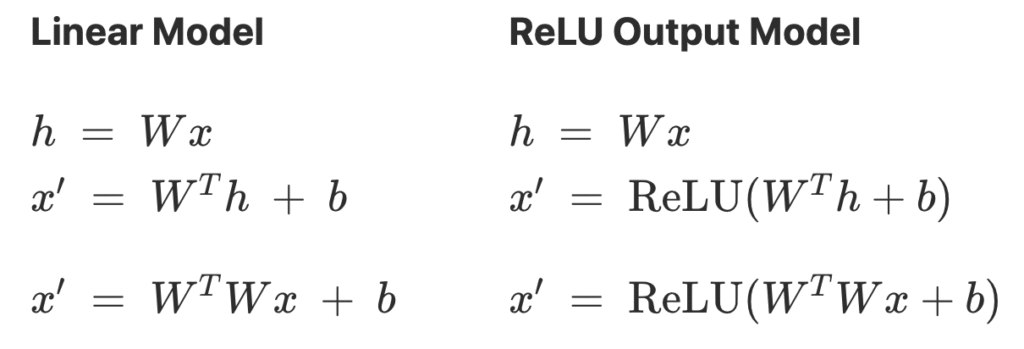

For most of the paper they consider two flavours of model. One is purely linear, the other applies a ReLU at the output to clean up the responses:

They optimize the weights $W$ to minimize the importance weighted loss,

The feature importances $I_i$ are typically set to exponentially decay so as to put more importance on the first few features. For example $I_i = 0.7^i$.

Geometry of Superposition

Uniform superposition

- To simplify the study they first consider uniform feature importance.

- $I_i = 1$ for each of the $n=400$ input features.

- Learned features has approximately unit norm, so quantified number of learned features as $\sum_{i=1}^n \|W_i\|_2^2 = \|W\|_F^2.$

- Measured superposition using Dimensions per Feature, $$ D \triangleq {m \over \|W\|_F^2}.$$

- The lower this number, the more input features are being crammed into the $m$ hidden units, hence more superposition.

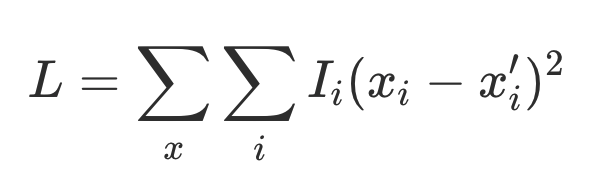

- Found, as expected, that $D$ decreases with sparsity, implying more superposition. Interestingly, the plot also had plateaus.

- Defined the feature dimensionality to measure how much each feature overlaps with the others $$D_i \triangleq {\|W_i\|_2^2 \over \sum_j (\hat W_j \cdot W_i)^2}.$$

- Feature dimensionalities indicate geometric configurations of features.

- If a feature doesn’t overlap with any others, $D_i = 1$.

- If it overlaps with an antipodal feature, $D_i = {1 \over 1 + 1} = {1 \over 2}$, etc.

- Overlaid the dimensions per feature plot (trace) with the feature dimensionalities (dots), and saw that plateaus corresponding to particular geometric configurations of features:

Non-uniform Feature Importance

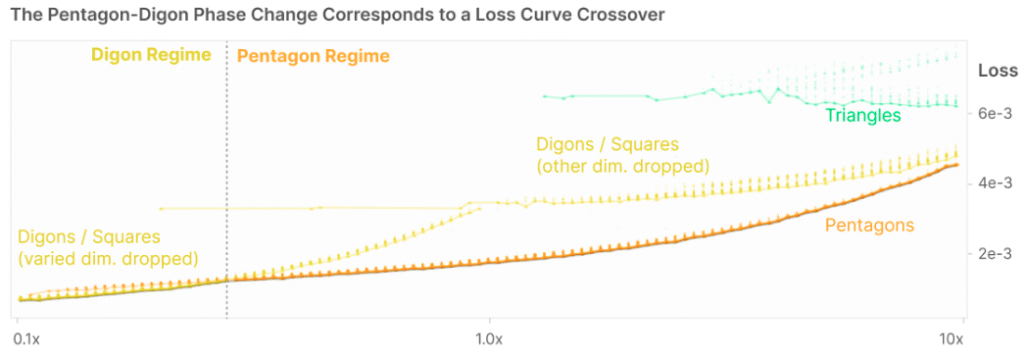

- They considered making one of the 5 input features more or less important than the others.

- As that feature decreased in importance, the lowest energy configuration transitioned from the pentagon to the diamond (digon):

- This makes sense – if an input feature is not very important to reproduce, the network will eventually drop it.

Correlated and Anti-Correlated Features

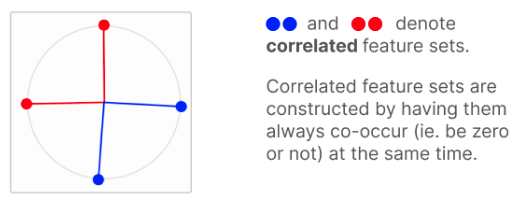

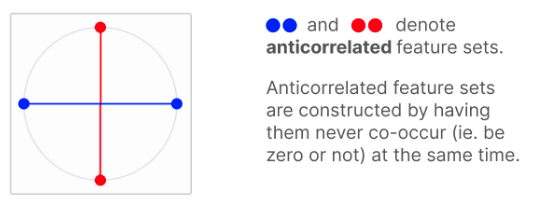

- Tried situations where features were correlated (always co-occur) or anti-correalted (one is present when the other is absent).

- Correlated features tend to be have orthogonal features:

- Anti-correlated features tend to be anti-podal:

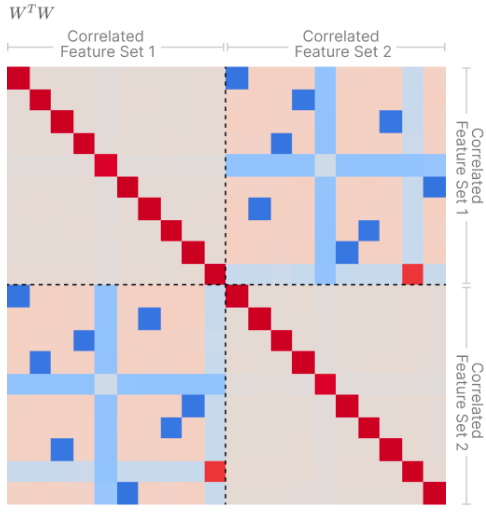

- Correlated features form “Local orthogonal bases”:

- All of these effects make intuitive sense:

- if features co-occur, we want to make them orthogonal to reduce overlap, reducing superposition.

- If they’re anti-correlated we can pack them into the same directions in space, increasing superposition.

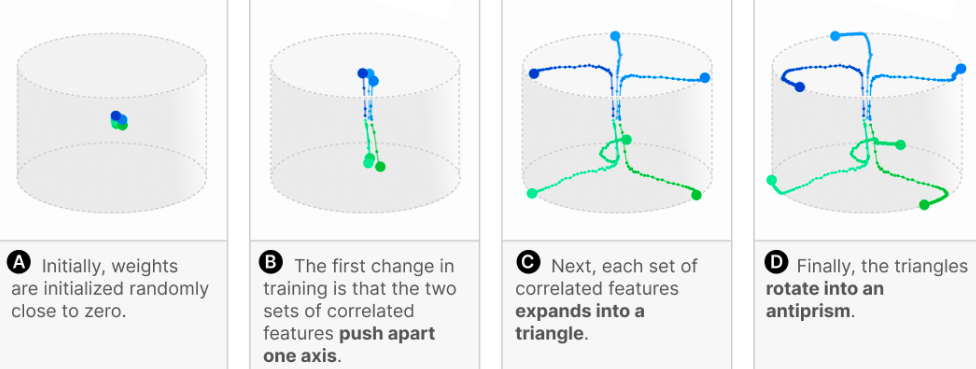

Superposition and Learning Dynamics

- Looking at $n = 6$ features compressed into $m = 3$ dimensions.

- Features were two groups of three correlated features.

- Optimization loss has plateaus, corresponding to qualitative changes in geometry:

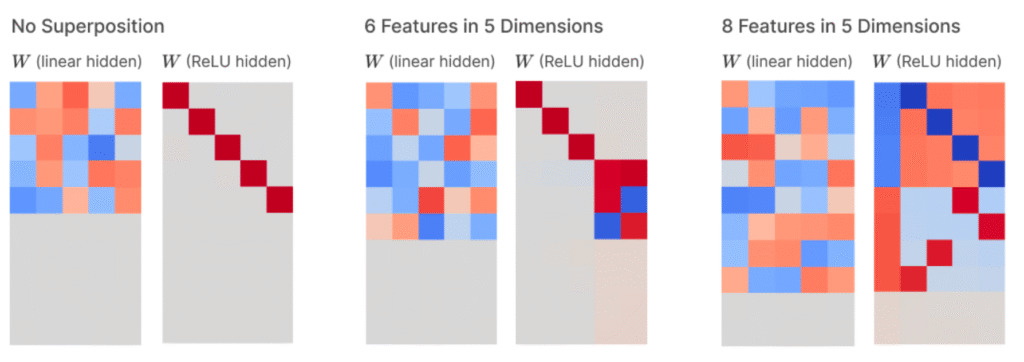

Superposition in a Privileged Basis

- Most of the results so far have a rotational redundancy.

- This is because what matters to the loss is not the weights, $W$, but their overlap $W^T W$.

- Therefore, any rotation $R$ in the latent space would produce the same loss.

- Because $(R W)^T R W = W^T R^T R W = W^T W.$

- This means that the weights themselves aren’t meaningful, hence why we’ve been looking at $W^T W$ throughout.

- In this section the authors introduce a privileged basis by applying a ReLU at the hidden layer.

- So $h = ReLU(W x \dots).$

- They find that the mapping from input features to hidden layer activations becomes interpretable.

- Dense inputs produce monosemantic neurons.

- Polysemanticity increases with the sparsity of the inputs.

Leave a Reply