A key experimental finding is the drop in pearson correlations from input to output. We’ve been trying to understand how this comes about using a linear model of the olfactory bulb, where the output is linear in the input. The linear factor is determined by the connectivity. We adjust the connectivity to make the input and output representations match. But to ease the mathematical analysis of the results, we’ve used the raw overlaps of the population responses, rather than the Pearson correlations. The latter require preprocessing the responses by mean subtraction and normalization. The mean subtraction is easy to handle, but the normalization is a nonlinear operation and makes the analysis more difficult.

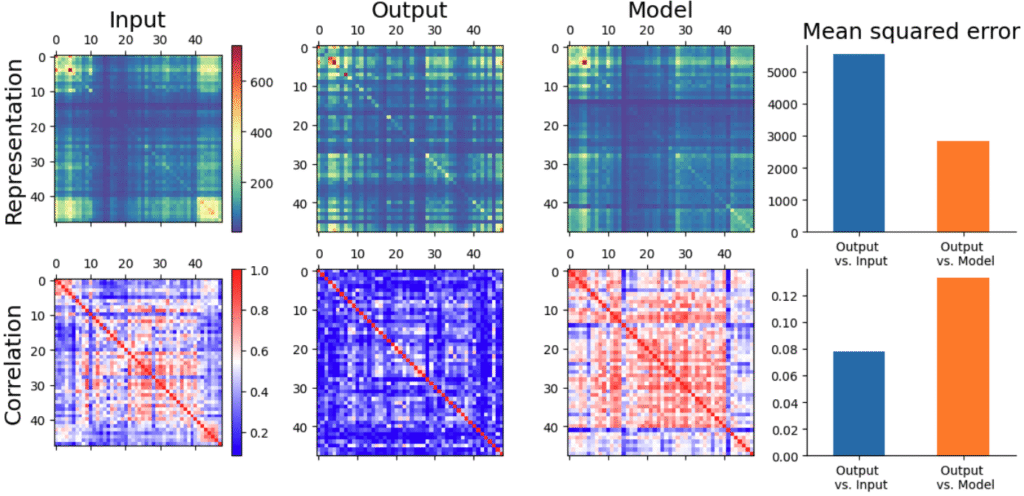

I had hoped that matching overlaps would also match Pearson correlations somewhat, but that doesn’t seem to be the case:

Matching correlations

The model does reduce the error in representations, but you don’t need the bar chart to tell that the correlation picture has gotten worse! So looks like we need to match correlations.

Subspace decomposition

Because Pearson correlations work on the mean-subtracted data, it’s useful to change basis to one that measures the mean component explicitly. That is, splitting up the $n$-dimensional response space as $$ \mathbb{R}^n = \underbrace{\text{span}\{\mathbf 1\}}_{\text{mean subspace}} \oplus \underbrace{\text{span}\{\widetilde{\mathbf U}\}}_{\text{correlation subspace}},$$ where $\widetilde{\mathbf U}$ is an arbitrary orthonormal basis for the space of mean-zero vectors, which we’ve called the correlation subspace.

We can then express a vector $\xx$ in this basis as $$ \xx = \mathbf{1} \overline{x} + \widetilde{\mathbf U} \tilde \xx.$$ The Pearson correlation of two vectors can be expressed in this basis as $$ \rho(\xx, \yy) = {(\xx – \overline{x})^T (\yy – \overline{y}) \over \|\xx – \overline{x}\| \|\yy – \overline{y}\|} = {\tilde \xx^T \tilde \yy \over \|\tilde \xx \| \| \tilde \yy \|}.$$ In otherwords, the Pearson correlation of two vectors only depends on their components in the correlation subspace, hence the name.

We can also consider how the feedforward linearity $\ZZ$ looks in this basis: $$ \ZZ_\rho = \begin{bmatrix} \bone^T \\ \widetilde{\mathbf U}^T \end{bmatrix} \ZZ \begin{bmatrix} \bone && \widetilde{\mathbf U} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \bone^T \ZZ \bone & \bone^T \ZZ \widetilde{\mathbf U} \\ \widetilde{\mathbf U}^T \ZZ \bone & \widetilde{\mathbf U}^T \ZZ \widetilde{\mathbf U} \end{bmatrix} \triangleq \begin{bmatrix} a_0 & \mathbf{a}^T \\ \mathbf{b} & \mathbf{B} \end{bmatrix}.$$

Each of the four terms above have an interesting interpretation:

- $a_0$ measures how much $\ZZ$ transforms the mean component into the mean subspace.

- $\mathbf a$ measures how $\ZZ$ transforms the correlation component into the mean subspace.

- $\bb$ measures how $\ZZ$ transforms the mean component into the correlation subspace.

- $\BB$ measures how $\ZZ$ transforms the correlations component into the correlation subspace.

Since the correlations only depend on the components in the correlation subspace, we can ignore the top row, and optimize $\bb$ and $\BB$.

Computing Correlations

Assuming an input $\xx$ is expressed in this basis as $\bone \overline{x} + \tilde \xx$, $\ZZ$ produces a correlation component of $$\tilde \yy = \bb \overline{x} + \BB \tilde \xx.$$ The correlation of two responses is then $$ \rho_{ij} = {\tilde \yy_i^T \tilde \yy_j \over \|\tilde \yy_i \| \| \tilde \yy_j\|} = { (\bb \overline{x}_i + \BB \tilde \xx_i)^T (\bb \overline{x}_j + \BB \tilde \xx_j) \over \|\bb \overline{x}_i + \BB \tilde \xx_i\| \|\bb \overline{x}_j + \BB \tilde \xx_j\|}.$$

It’s interesting to look at what happens when $\bb = \widetilde{\mathbf U}^T \ZZ \bone = \bzero.$ In that case, $$\rho_{ij} = {\tilde \xx_i^T \BB^T \BB \tilde \xx_j \over \sqrt{\tilde \xx_i^T \BB^T \BB \tilde \xx_i } \sqrt {\tilde \xx_j^T \BB^T \BB \tilde \xx_j }}.$$

This immediately tells us that $\BB$ can’t be a simple rotation, since that would leave the correlations unchanged. This makes sense – rotating all vectors by the same amount leaves their angles, and hence their correlations, unchanged.

This suggests applying a polar decomposition to $\BB$ to extract its rotational component, $$ \BB = \UU \SS \VV^T = (\UU \VV^T) (\VV \SS \VV^T) = \RR \HH.$$ Then $\BB^T \BB = \HH^T \HH = \VV \SS^2 \VV^T = \HH^2,$ and the correlation becomes $$\rho_{ij} = {\tilde \xx_i^T \HH^2 \tilde \xx_j \over \sqrt{ \tilde \xx_i^T \HH^2 \tilde \xx_i } \sqrt {\tilde \xx_j^T \HH^2 \tilde \xx_j }}.$$ This reduces our search to positive definite matrices, representing expansions or contractions of space along specific directions.

So, given the plausibility of this condition and how it simplifies the correlation computation, this might be a suitable configuration to analyze.

Connectivity interpretation

This condition $\bb = \bzero$ means $\ZZ \bone \propto \bone$, i.e. $\bone$ is an eigenvector. In such connectivity, the sum of the weights to each output unit are the same. To get the recurrent connectivity interpretation, notice that an eigenvector of $\ZZ$ is also an eigenvector of $\WW = \ZZ^{-1} – \II$. So in the recurrent setting such connectivity would mean that each mitral cell receives the same total synaptic strength from all other mitral cells. This might not be an unreasonable assumption, if we assume they all have the same synaptic strength budget.

Matching Correlations

To match correlations, we can define a loss function $$ L(\bb, \BB) = {1 \over 2} \sum_{j > i} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij})^2 + {\alpha \over 2} \|\bb\|_2^2 + {\beta \over 2}\|\BB – \II\|_F^2.$$ The regularization is needed because we have more cells than odours, so we can match the correlations exactly, and need to avoid overfitting. The regularization targets pull $\ZZ$ towards the identity.

Computing gradients

The gradients with respect to the parameters are \begin{align*} {\partial L \over \partial \bb} &= \sum_{j > i} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij}) \nabla_\bb \rho_{ij} + \alpha \bb,\\ {\partial L \over \partial \BB} &= \sum_{j > i} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij}) \nabla_\BB \rho_{ij} + \beta (\BB – \II).\end{align*} We therefore need the gradients of the correlations relative to the parameters.

Let’s first consider the vectors going into the correlation. Since $$ \rho_{ij} = {\tilde \yy_i ^T \tilde \yy_j \over \sqrt{\|\tilde \yy_i\|_2^2} \sqrt{\| \tilde\yy_j\|_2^2}},$$ \begin{align*}{\partial \rho_{ij} \over \partial \tilde \yy_i} &= {1 \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| \|\tilde \yy_j\|} \tilde \yy_j – {\rho_{ij} \over \|\tilde \yy_i \|_2^2} \tilde \yy_i \\ &= \boxed{{1 \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| } (\hat{\yy}_j – \rho_{ij} \hat{\yy}_i) .}\end{align*}

We can perform a few sanity checks on this expression. First, we expect the gradient along $\hat \yy_i$ to be zero – changing its magnitude shouldn’t change the correlation. And indeed, $$ \hat \yy_i^T {\partial \rho_{ij} \over \partial \tilde \yy_i} \propto \hat \yy_i^T \yy_j – \rho_{ij} = \rho_{ij} – \rho_{ij} = 0.$$

The contribution of the component along $\hat \yy_j$ should depend on its angle with with $\hat \yy_i$. If it’s perfectly aligned, the correlation shouldn’t change. If they’re orthogonal, then it should change a lot. Indeed $$ \hat \yy_j^T {\partial \rho_{ij} \over \partial \tilde \yy_i} \propto (1 – \rho_{ij}^2) = \sin^2 \theta_{ij}.$$ Notice also that this is non-negative, which represents how moving $\yy_i$ towards $\yy_j$ can only increase their correlation.

Finally, changes along any direction orthogonal to the $ij$ plane should not change the correlations. We can read that off immediately from the expression above.

Now for the gradients with respect to $\bb$ an $\BB$. \begin{align*} d\rho_{ij} &= \tr\{\nabla_{\tilde \yy_i} \rho_{ij}^T d\tilde \yy_i\} + \tr\{\nabla_{\tilde \yy_j} \rho_{ij}^T d\tilde \yy_j\}\\ &= \tr\{\nabla_{\tilde \yy_i} \rho_{ij}^T d\bb \overline{x}_i \} + \tr\{\nabla_{\tilde \yy_j} \rho_{ij}^T d\bb \overline{x}_j\} \end{align*}

From this we get \begin{align*} \nabla_\bb \rho_{ij} &= \overline{x}_i\nabla_{\tilde \yy_i} \rho_{ij} + \overline{x}_j \nabla_{\tilde \yy_j} \rho_{ij}\\ &= {\overline{x}_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| } (\hat{\yy}_j – \rho_{ij} \hat{\yy}_i) + {\overline{x}_j \over \|\tilde \yy_j\| } (\hat{\yy}_i – \rho_{ij} \hat{\yy}_j) \\ &=\boxed{\hat \yy_i \left({\overline{x}_j \over \|\tilde \yy_j\| } – \rho_{ij} {\overline{x}_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| }\right) + \hat \yy_j \left({\overline{x}_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| } – \rho_{ij} {\overline{x}_j \over \|\tilde \yy_j\| }\right). } \quad \checkmark \end{align*}

Similarily, \begin{align*} d\rho_{ij} &= \tr\{\nabla_{\tilde \yy_i} \rho_{ij}^T d\BB \tilde \xx_i \} + \tr\{\nabla_{\tilde \yy_j} \rho_{ij}^T d\BB \tilde \xx_j\} \end{align*}

From this we get \begin{align*} \nabla_\BB \rho_{ij} &= \nabla_{\tilde \yy_i} \rho_{ij} \tilde \xx_i^T + \nabla_{\tilde \yy_j} \rho_{ij} \tilde \xx_j^T\\ &=\boxed{\hat \yy_i \left({\tilde{\xx}_j \over \|\tilde \yy_j\| } – \rho_{ij} {\tilde{\xx}_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| }\right)^T + \hat \yy_j \left({\tilde{\xx}_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| } – \rho_{ij} {\tilde{\xx}_j \over \|\tilde \yy_j\| }\right)^T. } \quad \checkmark \end{align*}

Combining these parts, we can get the gradient relative to $\widetilde \ZZ \triangleq [\bb, \BB]$ as \begin{align*}\boxed{\nabla_{\widetilde \ZZ} \rho_{ij} = \hat \yy_i \left({\xx_j \over \|\tilde \yy_j\| } – \rho_{ij} {\xx_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| }\right)^T + \hat \yy_j \left({\xx_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\| } – \rho_{ij} {\xx_j \over \|\tilde \yy_j\| }\right)^T.} \quad \checkmark \end{align*}

Code implementation

The gradients above checkout, and I could implement a function that optimizes correlations accordingly. However, I already have existing code that optimizes covariances. I’d rather just modify that to do the correlation optimization.

The loss function I use in that code is $$L(\ZZ)= {1 \over 2M^2} \|\XX^T \ZZ^T \JJ \ZZ \XX – \CC\|_F^2 + {\lambda \over 2 N^2} \|\ZZ – \II\|_F^2.$$ Here $M$ is the number of odours, $N$ is the number of cells, $\JJ = \JJ^T\JJ = \JJ^2$ is the matrix that does mean subtraction, $\CC$ is the target covariance, and $\lambda$ is a regularization parameter.

To convert this to Pearson correlations, all we have to do is modify the first term to normalize out the variances, so something like $$L(\ZZ)= {1 \over 2M^2} \|\DD^{-{1 \over 2}} \XX^T \ZZ^T \JJ \ZZ \XX \DD^{-{1 \over 2}} – \CC\|_F^2 + {\lambda \over 2 N^2} \|\ZZ – \II\|_F^2.$$

The problem is that $\DD$ is a function of $\ZZ$, and the existing code doesn’t take that dependence into account. So we will have to implement a Pearson-specific version of the code.

We can keep the loss function similar, so $$ L(\ZZ) = {1\over 2M^2} \|\boldsymbol \rho(\ZZ) – \RR\|_F^2 + {\lambda \over 2 N^2} \|\ZZ – \II\|_F^2.$$

We can assume that we’re already in the correlation basis, so $\widetilde \ZZ$ is simply all but the first row of $\ZZ$. The first row of $\ZZ$ represents the mean-projection aspects of $\ZZ$, which are ignored in the Pearson correlation. So $$\nabla_{\ZZ[0,:]} L = {\lambda \over N^2}(\ZZ[0,:] – \ee_1).$$

For the remaining elements of $\ZZ$, we have $$\nabla_{\widetilde \ZZ} L = {1 \over M^2}\GG + {\lambda \over N^2}(\widetilde \ZZ – \II_1),$$ where $\II_1 = \II[1:,:]$ i.e. all but the first row of the identity, and $$\GG = \sum_{ij} (\rho_{ij} – R_{ij})\nabla_{\widetilde \ZZ} \rho_{ij},$$ and which we can hope to compute efficiently using einsum.

Specifically, using our expression for the gradient of the correlations above, we can write each term of the sum as $$ (\rho_{ij} – R_{ij}) \nabla_{\widetilde \ZZ} \rho_{ij} = (\rho_{ij} – R_{ij}) \left[ \hat \yy_i \left(\xx_j’ – \rho_{ij}\xx_i’ \right)^T + \hat \yy_j \left(\xx_i’ – \rho_{ij} \xx_j’ \right)^T\right],$$ where $$ \xx_i’ \triangleq {\xx_i \over \|\tilde \yy_i\|},$$ and similarly for $\xx_j’$. Letting $\veps_{ij} \triangleq \rho_{ij} – R_{ij}$, we get $$G_{pq} = \sum_{ij} \veps_{ij} \hat y_{ip} x’_{jq} -\; \veps_{ij} \rho_{ij} \hat y_{ip} x’_{iq} + \veps_{ij} \hat y_{jp} x’_{iq} -\; \veps_{ij} \rho_{ij} \hat y_{jp} x’_{jq}.$$

Let’s define $\hat \YY$ so that $\hat Y_{pi} = \hat y_{ip}$ (we define it this way instead of what seems more natural, the transpose, because our response matrices are typically in cells-by-odours format.) Similarly define $\XX’$. Then we can write the first term as $$\GG_1 = \hat \YY \mathbf{\mathbf{E}} \XX’^T,$$ where $\mathbf{E} _{ij} = \veps_{ij}$. Similarly, the third term is $$\GG_3 = \hat \YY \mathbf{E} ^T \XX’^T = \hat \YY \mathbf{E}\XX’^T,$$ since $\bE$ is symmetric.

For the other two terms, let’s first define $$e_j = \sum_j \veps_{ij} \rho_{ij}, \quad \ee = [\mathbf{E} \odot \boldsymbol{\rho}]\bone.$$ Then, using the symmetry of $\mathbf E$ an $\boldsymbol{\rho}$, the second and fourth terms equal $$ \GG_2 = \GG_4= – \hat \YY \diag{\ee} \XX’^T.$$

Collecting terms, we get $$\GG = 2 \hat \YY (\mathbf E – \diag{\ee})\XX’^T.$$

Now let’s see if we can extract even more structure by eliminating the hat and the tick. We have that $$\hat Y_{pi} = \hat y_{ip} = \tilde y_{ip}/\|\tilde \yy_i\|.$$ If we define the diagonal matrix $\DD$ such that $\DD_{ii} \triangleq \|\tilde \yy_i\|,$ then $$\hat \YY = \tilde \YY \DD^{-1} = \widetilde \ZZ \XX \DD^{-1}.$$ $\XX’$ is normalized the same way, so $$ \XX’ = \XX \DD^{-1}.$$ Note the lack of tilde in the latter.

Combining these expressions, we get $$ \boxed{\GG = 2 \widetilde \ZZ \XX \DD^{-1} (\bE – \diag{\ee}) \DD^{-1} \XX^T.}$$

This already looks a lot like the corresponding term when using the covariance objective. Let’s see if we can push it further. Let’s call $\XX_o$ and $\ZZ_o$ the inputs and transformation in standard coordinates. Then $\XX = \UU^T \XX_o$, and $\ZZ = \UU^T \ZZ_o \UU$, and $\widetilde \ZZ = \wt \UU^T \ZZ,$ so \begin{align} \GG &= 2 \wt \UU \wt \UU^T \ZZ_o \UU \UU^T \XX_o \DD^{-1} (\bE – \diag{\ee})\DD^{-1} \XX_o^T\\ &= 2 \wt \UU^T \ZZ_o \XX_o \DD^{-1} (\bE – \diag{\ee})\DD^{-1} \XX_o^T \UU.\end{align}

To convert this to a weight update in the cell space, we project the inputs on $\UU$, and project out along $\wt \UU$, to get \begin{align} \GG_o &= 2 \wt \UU \wt \UU^T \ZZ_o \XX_o \DD^{-1} (\bE – \diag{\ee})\DD^{-1} \XX_o^T \UU \UU^T\\ &= 2\JJ \ZZ_o \XX_o \DD^{-1} (\bE – \diag{\ee})\DD^{-1} \XX_o^T\end{align}

This is exactly the update we have for the covariance loss function, except the bit sandwichted in between the $\XX_o$ terms is different.

Generalized Correlations

We can consider a general case, where our loss term is $$ L(\ZZ) = {1 \over 2} \sum_{ij} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij})^2,$$ where $$ \rho_{ij} = \bphi(\ZZ \xx_i)^T \bphi(\ZZ \xx_j).$$ This would cover all the cases so far:

- Raw overlaps: $\bphi(\yy) = \yy$;

- Covariances: $\bphi(\yy) = \JJ \yy$;

- Correlations: $\bphi(\yy) = \JJ \yy/ \|\JJ \yy\|$.

Then we’d have \begin{align} dL &= \sum_{ij} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij})( (\bPhi_i d\ZZ \xx_i)^T \bphi(\ZZ \xx_j) + \bphi(\ZZ \xx_i)^T \bPhi_j d\ZZ \xx_j)\\ &= \sum_{ij} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij})( \bphi(\ZZ \xx_j)^T \bPhi_i d\ZZ \xx_i + \bphi(\ZZ \xx_i)^T \bPhi_j d\ZZ \xx_j), \end{align} from which we can read off the gradient as \begin{align} \nabla_\ZZ L &= \sum_{ij} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij}) (\bPhi_i \bphi(\yy_j) \xx_i^T + \bPhi_j \bphi(\yy_i)\xx_j^T)\\ &=2 \sum_{ij} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij})\bPhi_i \bphi(\yy_j) \xx_i^T, \end{align} since the error term is symmetric, and where $\bPhi$ are the Jacobians. These are

- Raw overlaps: $\bPhi = \II$;

- Covariances: $\bPhi = \JJ$;

- Correlations: $\bPhi = {\JJ \over \|\JJ \yy\|}(\II – \bphi \bphi^T).$

To derive the last one, \begin{align}d\bphi = {\JJ d\yy \over \|\JJ \yy\|} – {\JJ \yy \over \|\JJ \yy \|_2^3} (\JJ \yy)^T \JJ d\yy = (\II – \bphi \bphi^T) {\JJ \over \|\JJ \yy\|} d\yy,\end{align} from which we can read off the Jacobian above.

Note how the correlation Jacobian first subtracts out any component along the direction of the vector itself (since any such change wouldn’t change the unit vector), and then mean subtracts the result, since any change which was only along the mean direction would also not change the unit vector.

Now let’s see if we can derive our existing vectorized expressions for the gradients, in the two easy cases. For raw overlaps, the gradient is $$ \nabla_\ZZ L = 2 \sum_{ij} (\rho_{ij} – r_{ij})\yy_i\xx_j^T = 2 \YY \bE \XX^T,$$ where we’ve defined $E_{ij} \triangleq \rho_{ij} – r_{ij}.$ Similarly, for the covariance case, we get $$ \nabla_\ZZ L = 2 \sum_{ij} E_{ij} \JJ^2 \yy_i \xx_j^T = 2\JJ \YY \bE \XX^T.$$

These match the existing formulas I use. The general case is more complicated, $$ \nabla_\ZZ L = 2 \sum_{ij} E_{ij} \bPhi_j \bphi(\yy_i) \xx_j^T,$$ because $\bPhi_j$ depends on $j$.

ChatGPT pointed out that we can simplify a bit by bringing the sum over $i$ inside, so $$ \nabla_\ZZ L = 2 \sum_{j} \bPhi_j \left(\sum_i E_{ij}\bphi(\yy_i)\right) \xx_j^T = 2 \sum_{j} \bPhi_j \ss_j \xx_j^T.$$

The new terms $\ss_j$ correspond to $\YY\bE$ in the expressions above.

This expression seems quite general. Instead of requiring the user to specify normalization etc., we can just ask for a $\bphi$ and $\bPhi$ function, from which we can compute the rest, for all three correlation functions, and others that follow the general form.

$$\blacksquare$$

Leave a Reply